Complex life forms look different on the outside. But all plants, single-celled organisms, animals, and even humans at the simplest level are made up of similar material – cells that include nuclei.

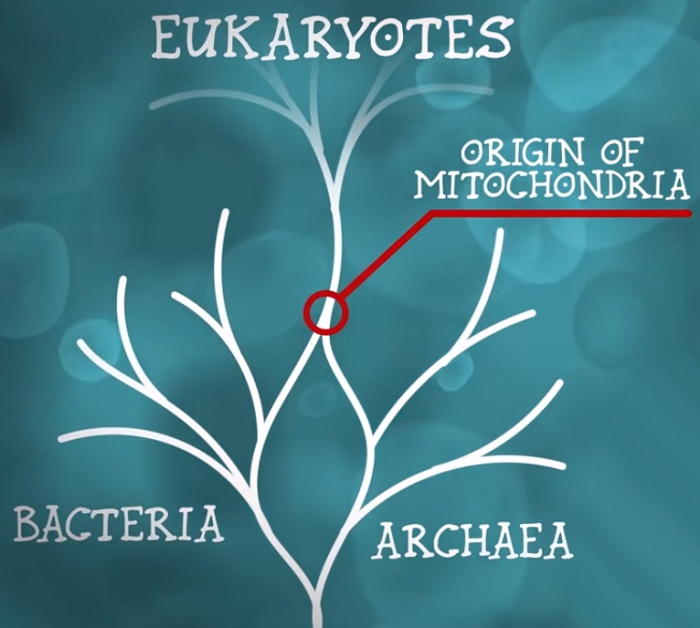

Eukaryotes, or nuclear, is the common name for all living organisms whose cells contain a nucleus. All organisms except bacteria and archaea are nuclear (viruses are also not eukaryotes, but not all biologists consider them living organisms at all). So, since many life forms, including humans, are eukaryotes, it is very likely that we all have a common ancestor. You and the apple tree growing in your garden are distant relatives, separated by several billion years and even more generations.

But eukaryotes did not exist for most of the history of life on Earth. Our planet was home to only two types of living organisms: bacteria and archaea. These two types of organisms are also grouped together under the name “prokaryotes.” These single-celled organisms reigned on Earth for the first two billion years after life appeared on Earth. But throughout the history of life on the planet, prokaryotes never became as large and complex as eukaryotes. That’s because they couldn’t store energy. Prokaryotes can only produce energy on their shell. Therefore, more energy production requires a larger shell area, and this requires a strong increase in cell size and this, in turn, requires even more energy to keep the cell alive.

Suppose a bacterium wants to increase all its linear dimensions by a factor of 3, then the shell area of this bacterium will increase by a factor of about 9 and the amount of energy produced will increase by the same factor. But, the volume of such a bacterium will increase by about 27 times, and the same amount of energy the bacterium will need to sustain its life. Thus, the bacterium will have three times less energy than it needs. This vicious circle would never be broken by prokaryotes on their own.

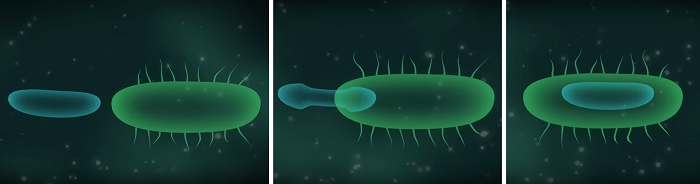

However, something unimaginable happened. An event so rare that it happened only once in the four billion-year history of life on the planet. One day, an Archaea cell encountered a bacterium and consumed it, but, for some reason, it would not digest the bacterium. We don’t know exactly why, but it was the first time that one living organism lived in symbiosis not together (side by side) with another organism, but within it. Such a phenomenon is called “endosymbiosis. Any living thing you see with the naked eye comes from this synthesis. By cooperating with its new home, which provided the bacterium with everything it needed, the bacterium was able to engage in one single thing: the production of energy, which had previously been so lacking in organisms for development. This is how the first mitochondrion was created, which was already a eukaryote.

These first eukaryotes had a surplus of energy, so they could grow and develop, experimenting with their incredible new abilities. Later, some of them absorbed a second bacterium, which learned photosynthesis. These eukaryotes later evolved into plants. Soon eukaryotes evolved into every animal and plant species on Earth, from jellyfish and chestnuts to sparrows and bears, and even us humans. We know it all started with the mighty mitochondrion because it still contains its own genome, a DNA strand like a prokaryote. We can find a third of our, human genes either in a bacterium or in an archaea.

So, in a world filled with bacteria and archaea, which collided with each other many times every second for the first two (of four) billion years of life on Earth, the eukaryotes have only had one origin story. So says the common ancestor of all eukaryotes, whose genome is still contained in the genomes of all plant species, animals, as well as humans. It happened thanks to such a simple but extremely rare event, when two branches of two different trunks of the tree of life joined into one, freeing life from the shackles of energy starvation, and giving nature the opportunity to create an infinite number of the most beautiful forms of life.